If you are new to birding and would like your observations to be available to scientists doing research on birds, you may want to consider uploading your findings to eBird. This is an online database created by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society to be a repository of millions of checklists from around the world along with media including photos, audio recordings and video. The first thing you will want to do before beginning to keep your records on eBird is to take the free eBird Essentials course, which will teach you what you need to know to get started.

The world of eBird is populated by scientists and amateur birders – professional birders too, who lead tours around the world – and a large host of volunteer reviewers whose job it is to keep the database as clean and free of errors as possible. One of the biggest challenges for these volunteers is to verify that the birds people say they saw ARE the birds people say they saw. This means examining any photographs or audio recordings that are submitted with the reports, and reading the descriptions included in the comments for that species. So your job is to make it as easy as possible for the reviewers to do their job. This means describing the bird and its behavior as carefully as possible. This documentation should include notes about the appearance of the bird, and it is very helpful if you can familiarize yourself with the basic external anatomy of birds so that you can use those terms to describe where the various colors of the bird appear. These include terms like “malar stripe”, “greater coverts”, “rectrices” and so forth, and most field guides include a drawing of a bird highlighting these areas. Having a camera is extremely helpful, and a nice “bridge” or super-zoom camera can be purchased without bankrupting you. Sound recordings are very easy to get with a free recording app such as Voice Record Pro, and Cornell offers instructions on how to perform simple editing and upload the recordings to eBird.

The process of documentation should be taken very seriously, because as a new birder you would probably like to be taken seriously yourself. It takes a lot of effort to gain a reputation as a careful, believable birder, and very little effort to lose that reputation. Even very experienced birders work hard at this – they want their local reviewer to have as easy a time as possible confirming their sightings and they take the time to write a description, even if it is a common, easily recognizable bird but it was seen during a season when it should not be in the area. Examples of descriptions that will immediately raise red flags for reviewers are “in a tree”, “I know what I saw”, “confirmed by Merlin”, and so forth.

Speaking of Merlin: this is a Cornell app that can be used to suggest identifications from photos or used in the field to “listen” to sounds and suggest identifications. It is based on many photos and recordings that have been added to the database from which it draws information to suggest what the bird might be. It is far from infallible and I consider it to be a crutch. I feel sad for all the people who jump into birding using Merlin and don’t take the time to track down the sounds they hear and figure out for themselves what those sounds are. Pedagogically speaking one learns sounds better without something to tell them what those sounds are. Let the birds tell you. Track them down in the field and spend some time listening and getting more familiar with the sounds. Listen to recordings of birds in your spare time to get to know the species in your area at different times of the year.

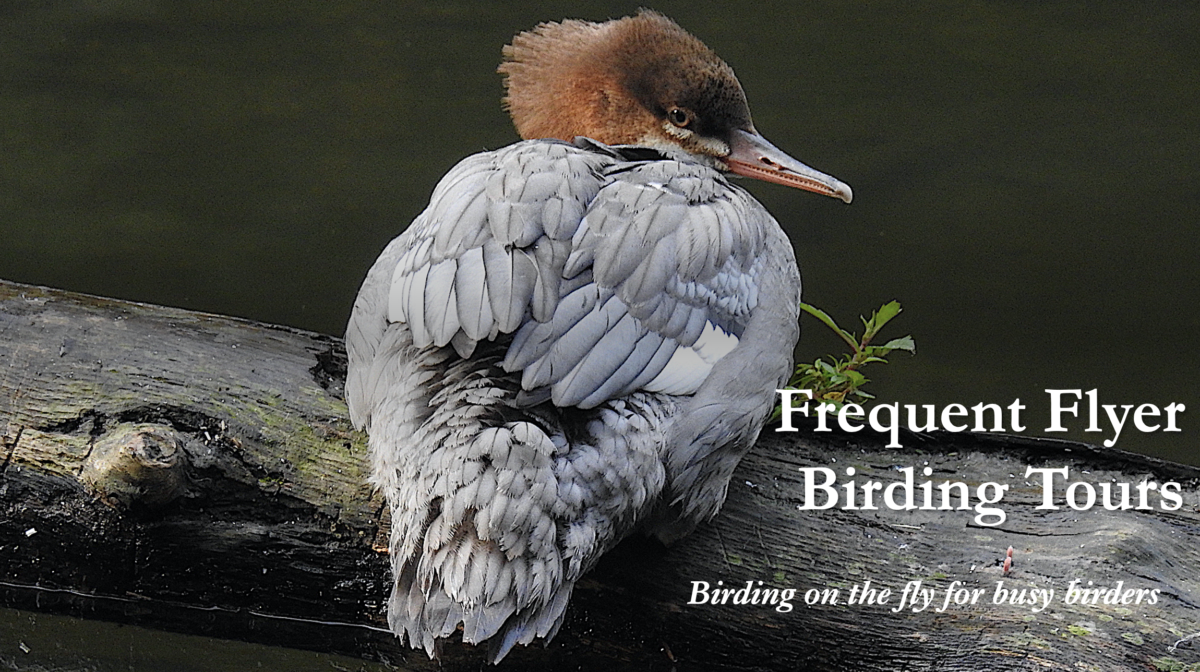

There is a word for people who see what they want to see or even make stuff up: “stringer”. For people who care about birding and their own reputations as reliable observers, stringers are horrifying, and they don’t fool anybody or least not for long. They are fortunately rare, but when they appear, it is disturbing. It is unclear what leads people to make things up –it must have to do with ego, and Cornell has set up a system that may push some people to try to see as many species as possible, with its automated list of Top 100 Birders. This may be the top for any geographical region such as country, state, county or province. You can opt out of this, but if you don’t opt out you should be particularly careful that every species you report is legitimate. I recently observed some ducks at a park that were being observed by somebody else at a more distant location. When I saw their list, I saw that it included two species that were not actually there: Red-breasted Merganser and Greater Scaup, both rarities for the season. What they were calling a scaup was actually a Ring-necked Duck, and the only mergansers there were Common Mergansers and one Hooded Merganser. Their report said they had photos, but they never uploaded them and their sightings were never confirmed. They still have them on their report, however, so their total of species they have seen for the year is inflated. Obviously, this does not help their reputation, and makes all their reports of rarities suspect unless they actually include media. I don’t say that all such observers intend to deceive anyone. They may have seen a report of a rarity, go out to look, and see something similar and get excited about it. As I said, they see what they are looking for rather than what is actually in front of them. This probably accounts for the vast majority of such misidentifications.

Be conservative in your reporting of rarities – be absolutely sure of the identification. Take photos or get recordings and compare them to photos and recordings in the eBird database or in field guides. Get help if you need it. Really observe the bird and write a careful description. This will increase your powers of observation and help you to become a better birder. It will also help in the painstaking process of establishing a reputation as a careful observer.

For more tips, read On Being a Good eBirder!